(Shared reading is a model that was developed by the reader organisation to bring people and books together.)

Shared reading groups

I’ve been a part of some very different shared reading groups; A university group, groups in addiction services, a group of volunteers, looked after children, a group of friends, secondary school children, and a group of mainly elderly members. From time to time, I’ve even done some shared reading with my own character creations – or what six-year-old me, would more confidently call, my imaginary friends. I tried to do some shared reading with my family once but my nan threatened to knock me out if I continued – probably one of the most aggressive responses, ever, to Wordsworth’s ‘Daffodils’.

The library group, of mainly elderly members, has been one of the most challenging for me. Most of the members came to the group with a joy of reading, looking to spend some of their free time engaged in something they enjoy and to connect with like-minded people. There is a great sense of community in the library and among the group. There have been powerful moments when the group have shared their personal stories of tragedy and success. They seem to find texts about family particularly engaging. When we read the The Summer Book, a lot of fond memories were shared about their own childhoods, and about time spent with their own grandchildren. Heart-warming stuff – leaving smiles all round.

Facing the emotional stuff

What I have found difficult, though, are the times when more emotionally complex characters and poetry are discussed, despite my best efforts to put forward different perspectives, these are people who have lived their lives and overcome their own challenges, and at a time before the therapeutic culture, we now find ourselves in, existed. So, poor Maggie Tulliver, for instance, ‘she is just too young to realise that life won’t always seem that dramatic. And George Eliot doesn’t write how most people think’. Trying to be courageous, I would then say how I did still feel like Maggie from time to time, and that I do think the way Eliot writes – I am a highly emotional and existential thinker. It’s good that I felt comfortable enough to share my own differences – that is the safe place shared reading can provide. It was good for me, too, to know that I was a part of this group despite thinking so very differently. What I did eventually share with the group, one day, when we were discussing another text involving emotional extremes, is that I probably relate to some of these experiences more, because I have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. And of course, almost everyone in the group, had a family member or a friend who had experienced mental health problems, and some group members were comfortable enough to share their own experiences of being unwell.

Not everyone does experience their emotional life to the same degree of intensity as Eliot describes. It does not mean you are mentally ill, though, if you do. My emotional life, in general, is one of intensity. There is a lot of talk about neurodiversity these days. In her book Divergent Mind Jenara Nerenberg links various neurodiverse experiences together through the key aspect of sensitivity. We now know, thanks to work from the likes of Elaine Aron and W. Thomas Boyce, that about 20 to 30 percent of the population is naturally more sensitive, this is true throughout the animal kingdom. It is not a disorder but it does mean being in that minority gives you a different experience of the world. Nerenberg describes how various forms of sensitivity are also crucial elements of Autism, ADHD, Sensory Processing disorder, and synaesthesia. Being highly sensitive in any form means that life often feels a lot more intense than it does for other people. I think it’s important that we are able to share these intense experiences and literature is often where they can be found.

It is true that such differences often give people unique abilities as well as difficulties. Some years ago, I was working at a summer school, for looked after children, at the reader. I was in charge of running round Calderstones park after a young boy with ADHD who had more energy than any child I’ve met. Yes, his hyperactivity and emotional dysregulation made joining in the activities with the other children very difficult, but he also had amazing hyperfocus when something interested him. One of those interests was football – he had an amazing ability for finding lost balls in the park – he found at least one every day, I never knew there were so many lost footballs hidden in a park. He had great determination too, it didn’t matter how hard it was to get to the ball, stuck up a tree, tangled up in nettles, floating on the lake, somehow, he devised a way to capture it. I was in awe of his ingenuity.

High on poetry

Literature isn’t about labels or social convention. It’s about whatever that thing is that makes life life – it is home, or infinite homes, made by meaningfulness. There are so many different perspectives on what it is to be human other than the mainstream medical, scientific, and political models. I’m an advocate of shared reading because it is through reading that I have found advocates for myself and my loved ones. When I was young, I often found fiction too difficult to concentrate on and I’m sad about all the great children’s books I missed out on but poetry was short enough and more challenging for me – I loved not understanding poems but still having that feeling of them doing something, for me, changing my insides, in mysterious and powerful ways. I knew I was different from my family – they wanted me to enjoy watching football with them and I wanted to get high on poetry. I’ve still not managed to turn any of them on to poetry, not even those that enjoy reading, my nan enjoys reading nostalgic novels but she wouldn’t entertain the power of nostalgia in Wordsworth. As I get older, the more I can accept the differences between myself and my family and the more I can appreciate the bonds between us – after all, as my nan says, ‘it wouldn’t do if we were all the same’.

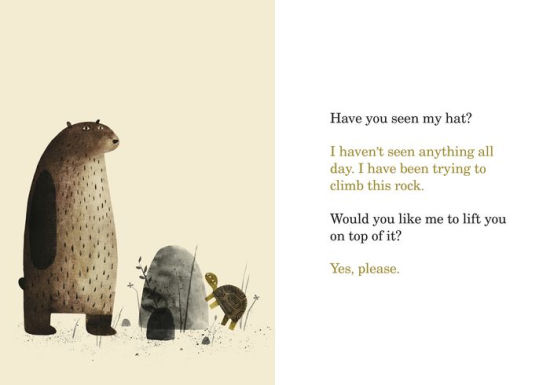

I want my hat back

I remember I want my hat back being read to the group of looked after children. These are children who have already faced challenges most adults would struggle with. You might expect them to have become hardened by such extremes but watching them enjoy that book was extreme innocence. I gave that book to my friend’s little girl – they love reading it together. He told me how the first time they read it they ended up having a rather philosophical discussion about what might have happened to the rabbit at the end – and whether or not it was right. A seemingly simple picture book allowed a parent and their 3-year-old to have a debate about morals in a fun and caring way. Such a conversation would probably have been a lot more difficult and upsetting had it been about something that happened in real life. Imagination is important at any age. Imagination transcends age, ability, experience.

Imagination – shared reading and learning

People with learning difficulties have differently wired brains too. Too often the power of imagination is forgotten about in schools. Too often how literature is taught to young people with learning difficulties is done in a way that assumes they cannot understand it, or certainly not as well as their peers. From my experience it is not necessarily that they don’t understand – it is that they have trouble tying to communicate their understanding, especially, in the standardised manner enforced in our education system. When I was working as a teaching assistant, and was left in charge of a low ability group, of 15-year-olds, I decided to do some shared reading with them. It was the end of the year and all the exams were over so we could read something not on the syllabus. I got them to sit down on the floor in a circle, which they found to be a novelty, I wanted it to feel more like story time, back when they probably enjoyed being read to. I was later told that the school would not approve of this but as long as I didn’t make a habit of it the head of English was prepared to turn a blind eye because she could see how engaged they all were. We read ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Not something anyone would’ve expected these students to understand or enjoy. They felt the fear of the wedding guest, they felt the cold of the ice, they felt the confusion of the mariner when he shot the albatross – they wondered why the crew thought it a good or bad omen and talked about superstitions they themselves followed even though they didn’t know why, like how everyone gets scared on Friday the thirteenth. One boy who is always drawing, sat and drew the ship as we read the poem – putting all the details of the natural world Coleridge describes – like the sun above the mast and the water snakes. Some of them were even confident enough to take over reading parts of the poem aloud. It’s one of my favourite memories of working in a school and one of my favourite memories of shared reading.

‘The self-unseeing’ – shared reading and recovery

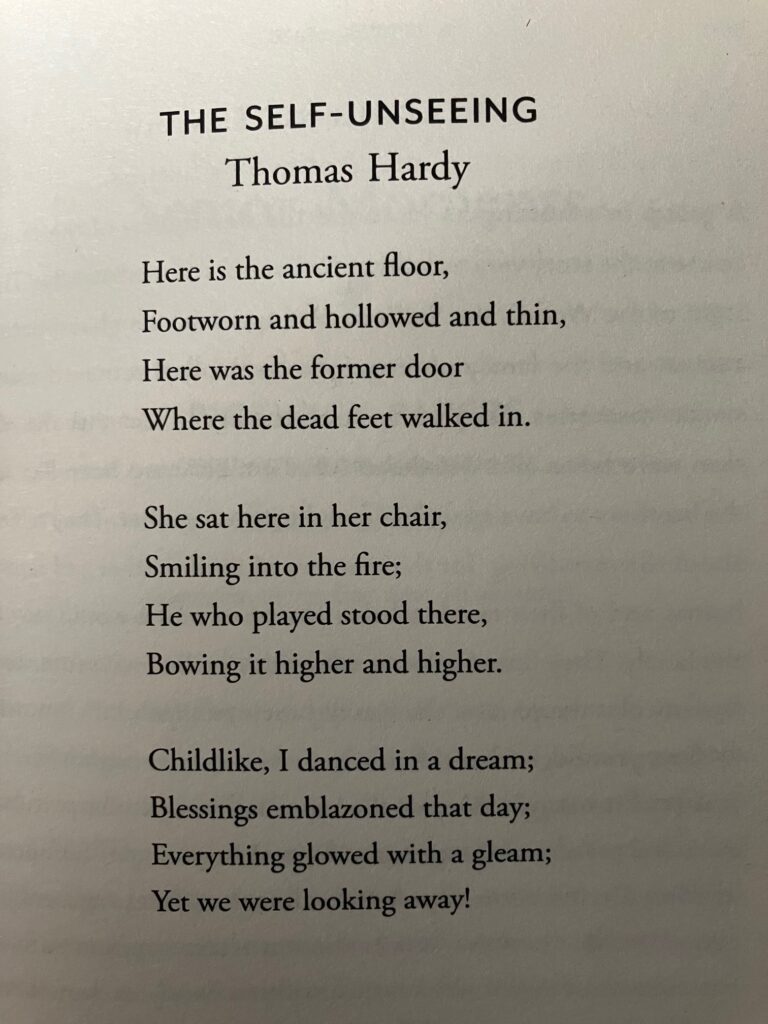

Another favourite memory of mine is from a group in an addiction service. It was one of the first sessions. We were reading ‘The Self-Unseeing’ by Thomas Hardy:

Most of the members were anxious because they couldn’t ‘get it’. I tried to reassure them – I told them that I hardly ever understand poems when I first read them either and asked them to tell me what jumped out at them, how it made them feel, or any images that came to mind? A man, who had previously been worried that the group would be too difficult for him to join in because he couldn’t read very well, was the first to speak. He said it reminded him of an uncle who had passed away and described him affectionately and as he spoke, he mentioned the words in the poem that had made him think about his uncle, like the fire and ‘the dead feet’. Someone thanked him for sharing his memory even though it sounded difficult for him and someone else congratulated him on how well he seemed to understand the poem and suddenly the whole group seemed to have been transported to inside the poem – the flow of conversation continued steadily onwards in that excitable sort of calm that comes from an atmosphere of people really listening to one another.

Working within the addiction services I found people there seemed to be a lot more at ease sharing their thoughts and feelings with one another, even though, they were often a lot more raw and difficult than those shared in other groups with people who had not had such harrowing experiences. And from my personal experience it felt a lot more beneficial to be able to share these aspects of our humanity without the focus being on drink or drugs or how to recover from drink and drugs. Yes, such groups are important, but they lack the depth of literature. Addiction makes life very narrow – literature can open life back up – sometimes gradually, and sometimes with a crowbar.

When I was doing the Reading in Practice course, I felt more like myself, and more connected to other people in general, than ever before. Once a week my mind was truly alive in an electric atmosphere of minds coming together sharing a joy of reading and literary thinking. There were times I could, literally, feel sensations in my brain – things fizzing or firing – it felt like parts of my brain were lighting up that previously had felt tacit but dark and ignored. This was a place I felt a real sense of belonging.

When I think about that course, or the many happy memories of being with family, or friends, I do feel ‘blessed’, in the way Hardy describes ‘blessings emblazoned’, and I feel able to bless in the way Coleridge described blessing the watersnakes unawares – blessing becomes something powerful and natural within us and literature helps bring that out, into the world, to share.

Shared reader leader volunteers, congratulations on your bravery, for being the person to hold the space for others to explore the depths of our shared humanity. Group dynamics can be tricky and it can be hard to be mindful of the wellbeing of everyone – for example I’ve been in a group were someone has had a very negative opinion of a character, that to my mind was very obviously depressed, and it is the reader leader’s job to try to show kindness towards such a character while at the same time not undermining the the perspective of any group member, so that the safety of the space is not compromised for anyone. Reader leaders are not health professionals or teachers or social workers but through literature they are helping to create more compassionate communities.

For more information about shared reading or to find a group to join visit thereader.org.uk

Further reading:

[This site contains affiliate links. A small commission might be earned at no additional cost to you but no money is accepted for reviews. Earnings contribute toward the running of the site and your support is much appreciated, thank-you.]